This Sunday I finish my third series in our adult class on Mary Magdalene, "There's Something About Mary." You can view the powerpoints of the first two classes on the church's web page.

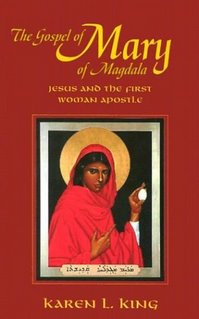

This week we look at the Gospel of Mary. Karen King of Harvard has written an excellent book on this gospel, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle.

The Harvard Gazette published an article about her work, Student of Early Christianities. Before she published her book, she wrote a preview about it and the importance of Mary for understanding Christian origins, Letting Mary Magdalene Speak.

One of the important implications of the discovery and publication of these other texts (such as the Nag Hammadi collection and the discovery of the Gospel of Mary in the 19th century) is that these finds force scholars (as well as the rest of us) to rethink Christian origins. King points out that the "master story" (her phrase) of Christian origins is like the Goldilocks and the Three Bears fable. The Goldilocks story of Christian origins goes like this:

- The apostles had the true teaching.

- Along come the heretics.

- The Jewish Christians had too much Judaism.

- The Gnostics had too little Judaism.

- "Orthodoxy" is "just right."

The writings we have in the canon represent the views of the writers. They are incredibly diverse within themselves (compare Paul and James, for instance). There was no rule of faith, no canon, no scripture. We don't know whose Paul's opponents really were or the opponents of the gospel writers or of the early church fathers except from what we could glean from them. Until now. Now we know some of these early writings in their own words. As King points out, we can see that categories such as gnostic or Jewish Christian were labels by the orthodox to distinguish heretics from the "true believers."

There was no gnostic belief system. There was no gnostic creed. There were different communities attempting to understand and communicate the historical Jesus in their various settings. For example, the Gospel of Mary was written in Egypt, far removed from Judaism and written in the philosophical setting of Plato and the Stoics. The writer of the Gospel of Mary would have thought of herself as Christian. In fact, there are great similarities between GMary and Paul as well as important differences. We won't be able to read and hear them accurately if we read their works through the lens of the Nicene Creed and canon.

What does this mean? For accurate history, and for the future of Christianity,

- I think it means that we ought to look at all of these early writings as early Christian texts.

- We should provide a critique of the "master story" of Christian origins as a theological fiction.

- We should remove false categories of "orthodoxy" and "heresy" when we read these texts.

- As all of the early Christian writers (canonical and non-canonical) sought to understand the Jesus movement in their social/political/philosophical contexts, we can do the same by drawing from the greater pool of early Christian literature to formulate an understanding of the transforming power of the mystery of Jesus in our time.

I really like the Goldilocks comparison. :) This really does seem to capture the problem with the orthodox party line on Christian history. The reality is that there was a diversity within Christianity from the very beginning, and one side won out over all the others. There were a lot of writings that almost made it into the Bible and that were included in early New Testament compilations but which were ultimately left out (often because they weren't written by an apostle, although in fact many writings that did make it in weren't written by apostles either, but pretended to be). For example--the Didache (whose version of the Lord's Prayer comes closest to the ones we use today), 1 Clement, the epistle of Barnabas.

ReplyDeleteThe orthodox story of Christian history has largely been a whitewash, because it serves orthodox interests. But it is important to open up our understanding of early Christian history.

Thanks, Seeker.

ReplyDeleteOne scholar suggests that the Didache was a very early work--around Paul's time, but I don't know too much about that. Even for those who still wish to privilege the canon for theological reasons would still benefit from an understanding of these other texts as they better help us understand the issues in the canonical texts as well.

BTW, I appreciated what you wrote about Borg's new book on your blog. I have just started it.

Warning: SATIRE AHEAD.*

ReplyDelete...It's not exactly fair to say that the Americans and the British were "right" and the Nazis and Japanese Imperialists were "wrong." What we need to do is move beyond those falsely dichotimizing categories (imposed - wrongly - by the militaristic victors) and acknowledge that at the begining of the 20th century, there was a breathtaking diversity of approaches to the issues of the Jewish problem, race, and national power. We have been misled by the censorious historical machinations of the winners of a world-scale ideological confrontation. Their editorial hand can be clearly traced as an obscuring "whitewash" over the nature of an early and acceptible multiplicity concerning governmental policies....

...So it becomes increasingly apparent that those who sided with a rather literal (read: narrow) interpretation of the preamble to the Declaration of Independence (now referred to as "civil rights leaders") were able to cast a pall of suspicion on those who preferred a more contextualized, historically informed reading of said articles. After all, can it be historically maintained that wealthy plantation owners - themselves slave holders - would actually believe that such declarations of human equality were meant to be literally and mechanistically applied to the situation in which we find ourselves presently?...

All quotes from the Revisionist's Guide to 20th Century American History, though it's not due for publishing until at least 3768 CE.

*Most liberals I know have to be told when something is said tongue-in-cheek to make a point.

Thanks, John. I'd be interested in knowing what you think of the Borg book.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate the ay this blog discusses alternatives views of jesus and the early church. However, it does appear that the books presented represent the far left of biblical scholarship, and give the impression that only liberals are serious biblical scholars. For another side, I recommend the writings of NT Wright, an Anglican scholar of some note. His book "The New Testament and the People of God" is quite good. Also, "The Real Jesus" by Luke Timothy Johnson and "Jesus Under Fire" are excellent starting points for those wishing to knoiw how orthodox theologians respond to the claims of the Jesus Seminar.

ReplyDeleteOf particular worth is the book "The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions," which features and extremely cordial debate between Marcus Borg and NT Wright.

Hi Freethinker,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment and the book recommendations. I have read those authors and had a class read the Borg/Wright book. They are all serious scholars.

What I find less engaging about Wright and Johnson, for instance, is that as you say, they are "orthodox theologians." Not that there is anything wrong with that, but their priorities are theological rather than historical. I am more interested in an historical approach.

Thanks again!

john